나는 Chris Fuchs와의 첫 인터뷰를했습니다. Fuchs는 University of Massachusetts Boston의 물리학 자이며 QBISM의 주요 지지자이며, 이론 이론의 많은 해석 중 가장 새로운 논란이 많은 QBISM의 지지자입니다. 양자 역학, 물리학자는 물질과 빛을 구성하는 전자 및 광자와 같은 기본 입자의 거동을 예측하는 데 사용하는 이론 역학, 실제로 입자와 관련이 아니라 신념에 관한 것입니다. 이론을 사용하는 사람에 대해. 그리고 여러 사람이 동시에 사용하고 있다면? 그런 다음 Qbism은 그들 각자가 자신의 신념뿐만 아니라 자신의 사실에 대한 자격이 있다고 말합니다. .

2020 년 8 월이었고 Fuchs와 나는 줌에 대해 이야기하고있었습니다. 그는 박제 안락 의자, 스포츠 와이어 트리밍 안경 및 유행성 머리카락에 부딪쳤다. 그는 나와 이야기하기 전에 QBism에 대해 자신을 교육했다고 주장했으며 기사, 인터뷰 및 비디오에 17 개의 링크를 보냈습니다. 이제 그는 나를 모두 버그로 만들었던 질문을 흐리게했을 때 그의 경력에 대한 일화로 가득 찬 이야기로 나를 다시 말하고있었습니다.

나와 같은 푸그는 50 대 중반에 있으며 얼굴이 둥글게 둥글다. 내 실수는 내 눈 앞에서 왁스처럼 왁스처럼 얼굴이 녹는 방식으로 즉시 명백했습니다. 순식간에 그는 Raconteur에서 강사로 변모하고 복잡한 실험실 설정의 사진을 올려서 저를 굽기 시작했습니다. "이 실험에서 들어가서 우연히 눈에 띄는 두 사람이 실험이 무엇을하고 있는지 동의합니까?" 그는 물었다. 이 강의는 화이트 보드에 스케치 된 정리로 마무리되었습니다. 나는 QBISM에 대해 혼란하기 전에 Fuchs를 더 잘 알기 위해 내 계획을 스카치했을뿐만 아니라, 박사 학위를 포함하여 물리학에 대한 나의 배경에도 불구하고 그의 주장을 따를 수 없었기 때문에 나는 내 시간을 항상 차고 있었다.

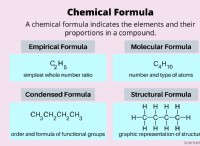

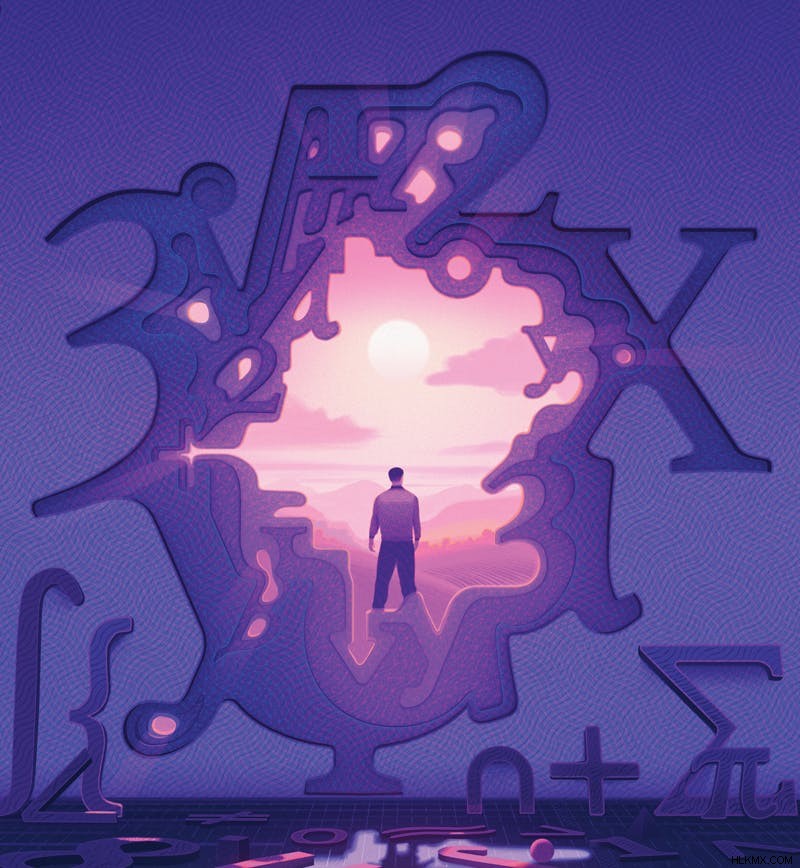

.사실, 내 교육은 내가 처음에 물리학에 들어간 이유와 마찬가지로 문제의 일부였습니다. 나는 초등학교에서 어려운 사건이었고, 지능적이고 호기심이 많지만 또한 갈등과 추가되지 않은 이야기의 혼란에 의해 가정 생활을 가진 정서적이고 충동적인 ADHD 아이도 어려웠습니다. 클래스 광대가되는 것은 선생님이 1 년이 걸리는 주말에 수학 통합 문서를 마쳤다는 것을 알게 될 때까지 가장 큰 야망이었습니다. 그로 인해 선생님이 보드에 방정식을 두드리면서 공황 상태에서 대수학 수업 뒤에서 자신을 찾아 냈고, 나는 그 편지에 당황했습니다. 도대체 x는 무엇입니까? 나는 주현절이 마침내 올 때까지 침묵으로 고통을 겪었다. x는 숫자이며 아직 모르는 숫자입니다. 행복감! 또한,“ x 를 넘어서 더 많은 아이디어를 이끌어내는 더 많은 문이 들어있는 곳의 문을 열었다는 느낌 .” 그 숫자와 상징과 기하학적 모양으로 그 아이디어의 궁전은 곧 놀이터가되었으며 피난처가되었으며, 모든“왜”질문에 답이 있었고, 내 남은 생애에 적용되지 않는 방식으로 일이 의미가있는 곳입니다. 나는 나중에 궁전이 진짜라는 약속으로 물리학에 끌렸다. 그리고 그 안에 어딘가에 숨겨져 있다는 것은 내가 너무 마술처럼 기각 한 신들과 마찬가지로 궁극적으로 모든 것을 설명 할 수있는 웅장한 방정식이었다.

.

내가 Fuchs와 대화 할 때 나는 물리학에 대해 덜 눈을 rese니다 (대학원은 당신에게 그렇게 할 것입니다). 그러나 궁전은 여전히 나의 행복한 곳이었습니다. 나는 감정이 위험하고 갈등에 대한 혐오감과 사람들로부터 특정 거리를 유지하는 데 번역 된 확실성에 대한 갈망을 발전 시킨다는 교훈을 내면화했습니다. 예를 들어 결혼은 오랫동안 다리가 너무 멀었습니다. 그리고 물리학의 법칙을 준수하는 입자 외에는 아무것도없는 세상이 망상을 자유롭게하는 것처럼 보였기 때문에 부분적으로 변화하는 능력을 의심했습니다.

동시에, 나는 양자 이론이 특성보다는 확률을 가진 입자를 묘사하는 방식 때문에 물리학이 세상을 설명 할 수 있다는 생각에 문제가 있음을 알 수있었습니다. 우리는 물리적 물체의 크기, 모양 및 위치가 구성 입자의 위치에 의해 설명된다고 생각하는 경향이 있습니다. 그러나 양자 이론은 그러한 특성을 입자에 기인하지 않으며, 대신 가 나타날 확률의 관점에서 설명합니다. 관찰 된 경우 위치를 갖는 것이 . 그럼에도 불구하고“관찰 된”의미와 양자 이론의 가능성의 뮤트와 일상적인 경험에서 객체가 가지고있는 견고한 형태로 속성을 구체화하기위한 관찰 중에 발생하는 것은 이론이 이론이 다루지 않는 질문입니다. 물리학 자들은 양자 이론의 설명에서“측정 문제”라고 설명합니다.

.양자 이론에 대한 다양한 해석은 측정 문제를 해결하기 위해 많은 이야기를 제공하지만, 그 중 어느 것도 만족하지 못했습니다. QBism의 이야기는 양자 이론이 현실을 직접 묘사한다는 것을 부인하는 전통의 최신 전통입니다. "세계는 6 개의 맛의 쿼크로 만들어지지 않았습니다."라고 그는 썼습니다. "꿈과 야망조차 물질이있는 세상입니다."

QBISM이 양자 역학에 대한 QBISM이“삶의 가치가있는 삶을 가치있게 만든다”고 말하는 Fuchs의 습관과 마찬가지로, 그런 종류의 Woo는 물질적 인 마음에 적기를 일으켰습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 QBism은 Nature Physics 을 포함한 최근 물리학 논문의 뗏목에 의해 진지하게 받아 들여질 가치가 있음이 분명했습니다. 제목은 "사실은 상대적입니다." 그런 아이디어를 찾은 것처럼 불안한 것처럼, 나는 Fuchs의 좋은 편을 타고 Qbist처럼 생각하는 방법을 배우기로 결심했습니다.

.

Fuchs와의 대화 몇 주 후, 돌이 많은 Adirondack 봉우리에서 높이, 심장이 신경으로 두근 거렸다. 나는 무릎을 꿇고 내 여자 친구 Martina의 주근깨가있는 얼굴을 올려다 보며 그녀에게 결혼 해달라고 부탁했다. 며칠 후, 나는 Fuchs와 이메일로 이야기를 공유했습니다. 내가 보통하는 일은 아니지만, 화가 조지아 오키프 (Georgia O'Keeffe)의 전 집이었던 뉴 멕시코의 고스트 랜치 (Ghost Ranch)에서 25 년 전 자신의 결혼식에서 사진을 보냈습니다. 그는 일주일 만에 키키와 사랑에 빠졌고 감정으로 극복했으며 6 개월 후에 적어도 1 년을 기다렸다는 약속에도 불구하고 반지 용 시가 밴드와 함께 제안했습니다. 나는 30 년 동안 6 년간의 독창적 인 아이디어에 익숙해지기 위해, 2 년 이상의 데이트, 내 규칙, 4 마일의 거친 4 마일 하이킹을 좋은 조치를 취하기 위해 내 자신의 제안과 대조를 주목했다.

.나는 Fuchs와 두 번째로 대화하고 개인적으로 그를 알게 된 것에 대한 초점을 유지함으로써 첫 인터뷰에서 회복했습니다. QBISM에 대한 나의 관심이 진실하다고 확신 한 후, 그는 철학이 중요한 윌리엄 제임스 (William James)의 4 권을 포함하여 이메일, 링크 및 독서 목록으로 저를 침해하기 시작했습니다. 내 QBISM 서신에 뿌려진 모든 방식의 개인적인 일화와 사진이 나왔습니다. 해변의 수영 트렁크, 뒷마당 흡연자, 그리고 그가 만든 반짝이는 고기의 20 대가있는 20 대가 마당에서 잡아 당긴 거대한 잡초를 들고 있습니다. "나는 내부 필터가 없다"고 말했다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 모든 홍수가 우호적 인 것은 아닙니다. Fuchs는 New York Times Magazine 을 위해 쓴 기사를 읽었습니다. 원자 물리학 자 닐스 보르 (Niels Bohr)와 베르너 하이젠 베르크 (Werner Heisenberg)“반 현실 주의자”의 견해에 반대했다. 그는 그 단어를“저주받은 오해”라고 언급했으며, 그 견해를 그 견해라고 부르는 나의 의견은“막 다른 골목”이라고 불렀습니다.

.QBism이 Fuchs의 아기라면 할아버지에게 가장 가까운 것은 Bohr이기 때문에 내 의견이 찌그러 졌다고 생각했습니다. Bohr는 1922 년에 전자가 원자의 핵 주위의 개별 궤도 세트 중 하나에 국한된 원자 모델을 고안 한 것에 대해 1922 년 노벨 물리학상을 수상했습니다. 당시의 물리 법칙과 공통점을 모두 무시한 아이디어는 전자가 전자를 점프해야했지만 궤도 사이. 그럼에도 불구 하고이 모델은 수소 가스에 의해 방출되고 흡수되는 빛의 색상과 같은 관찰 된 현상을 설명했으며, 1925 년 Heisenberg는 Bohr의 결과뿐만 아니라 다른 원자 현상도 예측 한 방정식을 제시함으로써 양자 이론을 고안했습니다. 이상한 점은 Heisenberg의 수공예가 순수한 수학적 조작 이었다는 것입니다. 그의 방정식은 광 주파수와 같은 관찰 가능한 수량만을 언급했으며 왜 을 설명 할 수있는 전자 거동에 대한 설명을 피했습니다. 그 주파수는 그 주파수였습니다.

한편, Erwin Schrödinger는 전자를 파도로 취급함으로써 Heisenberg가 만든 블랙 박스 내부의 작업을 밝히기를 희망했다는 이론의 자신의 버전을 개발했습니다. 그러나 Schrödinger가 파도 함수라고 불렀던 수학적 대상은 이제 종종 양자 상태라고 불렀으며, 그가 기대했던 방식으로 물리적 파도를 묘사하지 않았습니다. 대신, 물리학 자들이 이론의 확률을 요약하기 위해 사용하는 표준 장치가되었습니다. 물리학이 세계의 내면의 작업을 항상 영감을 얻었을 수 있다는 믿음이있는 Albert Einstein은 이론이 단순히 불완전하다고 생각했습니다. 그러나 Bohr와 Heisenberg는 이러한 발전의 교훈은 물리학이 다른 것을 묘사한다는 것입니다. Heisenberg는“양자 이론에서 수학적으로 수학적으로 공식화하는 자연의 법칙은 더 이상 입자 자체를 다루지 않습니다. 기본 입자의.”

"지식"은 양자 상태에서 인코딩 된 정보를 의미했습니다. 예를 들어, 주어진 원자가 관찰 될 때 특정 위치에 나타날 확률. Bohr는 물리학이 왜 그러한 제거에서 현실에 대한 설명을 제공 해야하는지에 대한 설명을 제안했습니다. 그는“우리는 우리 자신이 존재의 드라마에서 배우이자 관중이라는 것을 잊지 말아야합니다.”

.Bohr의 요점은 우리의 관찰이 변화하고 어느 정도 우리가 관찰하는 세계를 창조한다는 것이 었습니다. 양자 이론에 의해 뒷받침되는 아이디어는 물체의 관찰자와 대상 자체가 반드시 Schrödinger의 단어를 사용하는 것을 암시한다는 것을 암시합니다. 관찰되는 것은 물체 자체가 아니라 대신 객체, 관찰자 및 관찰 방법에서 만들어진 모든 선택의 일종의 매시업입니다. Bohr는 수소에 의해 방출되고 흡수되는 빛의 색상과 같은 이러한 매쉬업을 불렀으며, 양자 이론은 세상을 그대로 묘사하기보다는 물리학이 그러한 현상을 묘사해야한다고 결론 지었다.

이중 슬릿 실험이라고 불리는 양자 설명의 고전적인 사례에 나타나는 것과 같은 아 원자 입자의 많은 역설적 행동은 이러한 관점에서 탈신 될 수 있습니다. 이중 슬릿에서, 전자와 같은 입자는 두 개의 구멍이있는 스크린에서 발사되며, 미스터리는 때때로 스프레드 파인 것처럼 간섭 효과를 나타내는 방법이지만 다른 상황에서는 점과 같은 입자와 같은 작용입니다. 오늘날까지 아인슈타인이 옳았 고, 양자 이론이 불완전하고 소위“숨겨진 변수”(양자 역학에 나타나지 않는 입자 특성) 이이 행동을 설명하는 데 필요하다고 주장하는 물리학자가 있습니다.

.그러나 Bohr는 양자 현상의 명백한 모순이 세상을 관찰하는 것과는 별개로 세상을 묘사하려는 시도로 인해 우리가 할 수없는 일이라고 생각했습니다 . . 결론은“입자”,“파도”및“슬릿”과 같은 개념은 현실이 아니라 보어가“추상화”라고 불리는 것입니다. 이 경우, 전자는 입자 나 파도가 아닙니다. 그것은 단지 그것이 무엇인지, 또는 오히려 우리가 상호 작용할 때하는 일입니다. 그리고 무의미한 소리에도 불구하고 :단순히 문제에 대한 사실이 없습니다 그 중 썰매가 통과되지 않는 한 전자가 통과되었습니다.

Bohr의 물리학에 대한 급진적 인 재구성이었습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 Fuchs는 Bohr가 충분히 급진적이지 않았다고 주장했다.

Qbukis는 Fuchs-Speak에서 Fuchs가 그의 연구 그룹과 함께하는 주간 회의입니다. 나는 2020 년 10 월에 처음으로 참석했다. Fuchs는 그의 의자에 휩싸였다. 그의 유행성 머리카락은 내가 마지막으로 그를 보았을 때보 다 2 개월 더 길었다. Qbukis가 항상 시작한 무작위 농담 기간 동안 Fuchs는 좋아하는 날개 노래 인“Let Me Roll It”을 제기하고 그룹을 위해 연주했습니다. Crosstalk가 가라 앉았을 때, Fuchs는 브라질에서 그와 함께 일하는 젊은 박사후 자크 인 Jacques Pienaar에게 QBism에 대한 라이벌 해석을지지하는 물리학 자 그룹의 최근 논문에 대한 논의를 이끌어달라고 요청했습니다. 중심적인 질문은 Wigner의 친구를 다루는 방법이었습니다.

모든 사람들은 Schrödinger의 고양이에 대해 들었습니다. 고양이가 유독 가스를 방출 할 50-50 확률이있는 양자 장치가있는 상자에 고양이가 잠겨있는 사고 실험입니다. 혼란의 요점은 양자 이론의 양자 상태가 고양이를 죽은 또는 살아있는 두 가지 결과의 중첩으로 특징 짓는 것입니다. 대중 문화 그러한 중첩에서, 이론은 실제로 그 질문에 대해 말하지 않으며, Bohr는 물리학이 인간의 경험을 묘사하는 것으로 제한되어야한다는 것을 상기시켜 줄 것입니다.이 경우 관찰자가 상자와 외모를 열 때 관찰자가 보는 것 Schrödinger는 1935 년 에이 시나리오를 출판했습니다. 이상하게도, 그것은 1/4 세기가 걸렸고 또 다른 노벨상 수상자는 회고 적으로 명백한 질문처럼 보이는 것을 묻습니다.

그것이 헝가리 물리학 자 Eugene Wigner가 가상의 사람을“친구”라고 부르는 일입니다. Wigner는 친구이기 때문에 빛이있는 장치의 독을 바꾸 었습니다. Wigner의 분석 결과는 상자의 친구가 예를 들어 녹색을보고 양자 상태가 그 결과를 반영해야한다고 믿는 반면, Wigner는 Schrödinger 's Cat의 관찰자와 같은 위치에서 상태가 두 색상의 50-50 중첩이라고 생각합니다. Wigner의 상태는 이중 슬릿 실험에서 그 상태와 유사하며 Bohr 스타일의 추론에 의해 빛의 색상에 관한 문제가 없음을 나타냅니다. 결론은 Wigner의 친구 은 을 알고 있다는 것입니다 녹색 불빛은 사실, 동등한 정당화와 함께 사실입니다. 은 그렇지 않습니다. 이 결과는 Bohr 's와 Heisenberg의 양자 이론이 인간의 지식과 경험, 즉 질문에 대한 답변에 관한 것이라는 문제의 문제를 강조합니다. 지식? 그리고 의 경험?

“사실은 자연 물리학의 상대적”논문입니다 물리학자인 Caslav Brukner가 저술 한 Wigner의 친구의 변형에 중점을두고, Quantum 이론의 모순 능력은 사실이 실제로 공간과 시간이 아인슈타인에 의해 발견 된 것처럼 관찰자와 관련이 있음을 암시하기에 충분히 깊어 졌다고 주장합니다. 이것은 Bohr와 Heisenberg조차 예상했던 것보다 더 기괴한 결론이지만 새로운 방식으로는 그렇지 않습니다. 예를 들어, 양자 이론에 대한 많은 세계 해석은 모든 신체적 상호 작용의 가능한 모든 결과가 발생하고, 우주가 모든 모순적인 사실을 수용하기 위해 끊임없이 분열되고 있으며, Wigner의 친구의 경우 빛과 친구가 두 가지로 나뉘어져 있으며, 다른 사실 (레드 vs. 녹색)으로 분리 된 삶으로 살아 가고 있습니다.

QBISTS는 라이벌의 논문을 지정했습니다. Fuchs의 오랜 공동 작업자 인 Marcus Appleby는 시드니의 소파에서 기대고“불일치”라고 선언했습니다. 매사추세츠 대학교 보스턴의 Fuchs와 같은 물리학자인 Blake Stacey는 두 물리학자가 실험 결과에 대해 완벽하게 의사 소통 할 수 있다는 논문의 가정에 좌절감을 느꼈습니다.

Qbists의 말을 듣는 것은 나에게 다른 방법으로 보이는 것처럼 보일 수있는 것에 대해 말할 수있는 종이는 내가 더 진보 된 문명, 외계인, 아마도 대부분의 물리학 자들이 당연한 것으로 여겨지는 구내로 고양되고 순진한 것으로 간주되는 것처럼 느끼게 만들었습니다. Qbist Coup de Grace를 전달한 것은 Fuchs였습니다. 저자는“도대체 확률이 무엇을 의미하는지 걱정하지 마십시오.”

.회의에서 로그 아웃하면서, 그 의견은 QBism의 정의 관찰을 포착하는 것으로 저를 강타했습니다. 문제는 철학자들과 수학자들이 양자 이론 이전 이래로 Bertrand Russell이 말했듯이“아무도 그 의미가 무엇인지는 거의 없다”고 토론하고 있다는 것입니다.

.

사랑, 아름다움, 좋은 맛과 같은 확률은 객관적인 정의에 저항합니다. 뉴턴의 법칙에 따라 동전 던지기와 같은 상황에서는 쉽게 볼 수 있습니다. 뉴턴의 법은 실제 무작위성이 관여하지 않으며 비디오 카메라와 적절한 프로그래밍 컴퓨터로 무장 한 사람이 헤드에 50 % 확률을 부여하는 더 캐주얼 관찰자보다 훨씬 유능한 결과를 훨씬 더 유능하게 예측할 수 있다고 보증합니다. 그러나 불확실성이 본질적 인 양자 사례에서도, 경험, 지식, 선호도, 심지어 성격에 따라 사람이 할당 한 확률이 어느 정도 주관적이라는 사실을 피할 수는 없습니다.

QBism의 핵심 교리는 확률이 완전히 이라는 것입니다 주관적으로, 그들을 할당하는 사람에 대한 개인적인 신념은, 각각은 0과 1 사이에 가치가 있어야한다고 말하는 것과 같은 확률 이론의 규칙에 의해서만 제한됩니다. 확률에 대한 이러한 해석을 "개인주의 베이지안"이라고합니다. QBism의 "Q"는 Quantum과 Bayesian의 "B"를 나타냅니다 (또는 적어도 Fuchs가 그 연결을 버리고 QBism을 KFC와 같은 자체 브랜드로 만들 때까지). Fuchs의 결혼과 마찬가지로 1990 년대 중반 뉴 멕시코 대학교 (University of New Mexico)에서 물리학 자 Carlton Caves에서 공부하고 양자 이론의 바닥에 도달하기로 결심했을 때 1990 년대 중반에 시작되었습니다. 개인 주의적 베이지안 관점에 대한 퓨즈를 얻은 것은 동굴, 특히 그의 박사후 루레이거 샤크 (Ruediger Schack)였으며, QBism은 세 가지 사이의 협력에서 벗어났다.

.양자 이론의 의미에 대한 QBism의 설명은 핵심 교리에서 나옵니다. 예를 들어 원자의 양자 상태가 원자 을 설명하는 것으로 간주되는 경우 , 기본적으로 상태가 진화하는 방법에 대한 많은 규칙 인 양자 이론은 원자가하는 일을 예측하기위한 시스템에 해당합니다. 그러나 확률이 신념으로 해석되면 양자 상태도 신념이되고 전체 이론은 다른 동물로 변형됩니다. 그런 다음 원자 상태는 이론의 사용자를 설명합니다. , 특히 원자를 조사함으로써 그들이 경험할 수있는 것에 대한 그들의 믿음. 그리고 이론의 규칙은 그러한 신념을 지배하여 사용자에게 최적화 방법에 대해 알립니다. Fuchs는 Quantum 이론을“사고의 법칙”과“당신이 속한 세상에서 더 나은 결정을 내리는 시스템”이라고 부릅니다.

.이 관점은 Wigner의 친구의 모순을 해결합니다. Wigner와 그의 친구의 상태는 잠재적으로 다른 미래 경험에 대한 사용자의 신념을 나타 내기 때문에 다릅니다. Qed.

QBism이 양자 수수께끼를 쫓아내는 방식이 너무 쉽습니다. 그리고 침몰하는 데 시간이 걸렸습니다.

어느 날, 유행성 겨울의 깊이에서 새로운 약혼자와 함께 숲 속의 집에 구멍을 뚫었습니다. 나는 창문 밖을보고 Titmouse가 눈 속에서 뛰어 다니는 것을 보았습니다. 나는 충격으로 QBISTS가 내가 Titmouse라고 부르는 것이 실제로 세상의 일이 아니며 이것이 측정 문제에 대한 그들의 해결책의 핵심이라는 것을 깨달았습니다. QBism은“관찰”은 단순히 창문 밖을보고있는 것과 같은 인간의 경험이라고 말합니다. 그러한 관찰이 어떻게 Titmouse의 위치와 다른 속성과 같은 사실을 Quantum Murk에서 나오는 지에 대해 Qbism은 그 속성이 이라고 말합니다. 객관적인 사실뿐만 아니라 내가 경험을 설명하기로 생각했던 믿음은 보어의“추상화”와 유사하지만 지금은 나에게 개인적입니다. 나는 QBISM에서 무형 양자 세계와 콘크리트 일상 사이에 분열이없는 이유를 갑자기 감사했습니다. 일상적인 세계의 모든 것이 내 일상의 모든 것부터 내 아이폰에 이르기까지, 양자 상태와 같은 횡격증을 가지고 있습니다.

Fuchs의 철학적 영웅 인 William James는 Quantum Mechanics 이전에 실용주의라는 지식 이론의 일환으로 수십 년 만에 말했다. 그와 다른 실용 주의자들은 다윈의 후, 남북 전쟁, 19 세기에 현실의 개념이 반드시 지브를 지키는 것은 아니었던 과학 이론의 확산으로 우리의 아이디어, 이론, 신념이 근본적인 현실을 반영 할 수는 없지만 동시에 현실의 존재에 의문을 제기하지는 않았다고 결론 지었다. 대신, 그들은 우리의 아이디어가 우리의 경험에서 비롯된 것이라고 주장하고, 세상을 탐색하기 위해 우리가 구성하는 도구이며, 그들의 진실은 그들이 얼마나 잘하는지에 의해서만 판단 될 수 있다고 주장했습니다. Fuchs가 제공 한 참고 문헌을 읽을 때, 나는 경험이 때때로 고통스러워하더라도 이러한 주장에 동정심을 느꼈습니다. 야고보에게, 나는 아이디어 궁전에서 현실의 기초를 찾는 꿈의 꿈을 꾸는“부드러운 합리주의 자”였다.

아우.

그럼에도 불구하고, 양자 이론이 QBism이 말한 것처럼, 신념에 관한 모든 것이 현실이 있었던 물리학에 끔찍한 구멍을 남기고 있다면. 아인슈타인은 보어의 양자 이론에 대해 똑같이 느꼈으 며, 그는 한때 동료에게 아무도 그것을 관찰하지 않으면 달이 없다고 믿었는지 물었다. “물론 @#$%&! Fuchs는 2021 년의 물리 회의에서 질문에 대한 응답으로``달 '이라는 단어와 그것이 포함 된 문장이 의미가 없어 질 것입니다.“현실은 문장 형성이 될 필요는 없으며, 양자 이론이 그렇지 않다고 생각하는 경향이 있습니다.”

.그것은 내가 Titmouse에 대해 내가 깨달은 달에 대해 Fuchs의 말을하는 방법이었습니다. 그는 하나의 Qbuki에 와인 잔을 마신 것처럼“기대의 묶음”이라고 부르며“와인 잔이면 내가 떨어 뜨리면 파손되어야합니다. 와인 잔이면 액체를 고정해야합니다.” 그러나 어떤 대상이나 현실에 관해서는 달이나 타이 마우스에 대한 우리의 경험이 뒤에있을 수 있습니다. 글쎄, 우리는 그것을 @#$%&라고 부를 수도 있습니다! 우리는 경험 이외의 다른 방법으로, 다른 방법으로는 아무 말도하지 않기 때문입니다. QBism의 핵심 교리는 양자 이론이 우리가 세상의 일부 객관적인 상황보다는 우리의 마음 속에서 우리가 생각하는 현실과 달의 현실을 설명한다는 것을 암시합니다. 제임스와 보어는이 현실이 우리의 경험에서 비롯된 것이라고 주장했다. 그리고 Wigner의 친구는 한 Qbist 논문이 말한 것처럼이 현실은“현실은 대리인마다 다릅니다.”라고 보여줍니다. Qbists는 때때로 현실에 대한“신의 시야”가 존재하지 않는다고 말 함으로써이 모든 것을 요약합니다.

QBISM이 측정 문제로 분배 한 효율성을 높이 평가 한만큼 나는 여전히 어려움을 겪었습니다. 물리적 세계에는 객관적인 사실이있는 것 같습니다. 밤에 책상에 노트북을 남겨두면 여전히 아침에 거기에있을 것이라는 사실이 있습니다. 마르티나를 내 사무실로 전화하면 그 위치를 확인한다는 사실이 있습니다. 물리학 자들이주기적인 테이블에서 맑은 하늘의 푸른 색에 이르기까지 물리학 자들이 Quantum 이론을 설명하기 위해 Quantum 이론을 찾는 것은 말할 것도 없습니다. QBISM이 옳고 나와 다른 사람들이 물리적 세계라고 부르는 것은 주관적인 신념에만 해당되는 경우 어떻게 그러한 사실을 설명합니까?

3 월 금요일 오후 였고 이번에는 Qbuki Zoom Call에 12 명이 나이 외에 쿠크, 회색 까마귀와 그의 평범한 의자, 그의 Qbist 공동 작업자, 그리고 QBism에 흥미를 느꼈지만 아직 확신하지 않은 나와 같은 사람들이있었습니다. Fuchs의받은 편지함은 QBism의 신체적 사실에 대한 설명을 이해하려고 노력하는 이메일로 막히게되었으며 마침내 Qbuki를 직접 실행하고 그룹에 내 질문을했다고 제안했습니다.

.나는 이중 슬릿의 전자와 같은 작은 것들이 속성을 갖는 측면에서 설명을 무시하는 방식으로 어떻게 행동하는지에 대한 이분법에 어려움을 겪고 있었는데, 와인 안경과 같은 큰 것들 는 입니다. 크기와 모양과 같은 사실 측면에서 설명 할 수 있습니다. 사물에 대한 사실이 그 부분의 사실로 줄어든다는 상식적인 생각은 어떻게 든 무너져야합니다. 그러나 여전히…

"우리는 와인 유리라는 기대의 묶음이 유리를 구성하는 원자의 기대 묶음과 밀접한 관련이 있다는 생각을 실제로 거부해야합니까?" 나는 물었다.

Fuchs는“매우 자주, Bob”라고 대답했습니다. Fuchs는 느리게 학생이 인내심을 갖는 선생님처럼 들리며,“여전히 작은 사람들을 더 기본적인 것들과 더 큰 사람들을 더 파생 된 것들로 내려 놓는 것처럼 느껴집니다.”

.“내가 원자를 유리보다 근본적인 것으로 생각하는 이유”라고 설명했다.

이로 인해 그룹의 반박이 발생했습니다. 누군가가 지적한 하얀 빛을 구성하는 단순한 퇴적 단일 색상은 철학적으로 복잡한 무한대 개념을 필요로합니다. Quantum 이론에 따라 기본 입자조차도“무한히 복잡합니다”라고 말합니다.

내 요점의 손상을 평가하기 전에 Fuchs는 주제를 변경했습니다.

"Bob은 종종 세계의 안정성을 불러 일으킨다"고 말했다. 그는 랩톱이 밤에 머무르는 방식부터 과학 실험의 반복성에 이르기까지 내가 설명한 신뢰할 수있는 규칙 성의 종류를 언급했다. Fuchs는 자동차의 행복한 가족이 트럭에 맞는 할리우드 영화를 언급했습니다. 그는 18 세기 철학자 데이비드 ume의 주장을 제기했다.

"태양은 항상 일어나지 않을 때까지 상승한다"고 그는 말했다. "할 수 없을 때까지 가족 안정성을 믿을 수 있습니다."

할리우드? 자동차 충돌? 나는 그의 요점을 보지 못했습니다. 그러나 다시, 물리학 자, Qbissel 및 Pienaar의 아내 Gabriela Barreto Lemos는 Rio의 곳에서 매우 뜨거웠으며, 에어컨이 그렇지 않을 때까지 효과가 있었으며 최근에 모든 것이 어떻게 변화하고 있는지 알아 차렸다 고 말하면서 맹세했습니다.

.그녀는“정말 놀랍습니다. 그녀는 손으로 폭발을 흉내 냈다. “모든 것이 매우 안정적으로 보이고, 당신은 그것이 안정적이지 않다는 것을 알고 있습니다. 나는 안정적이지 않습니다. 당신은 안정적이지 않습니다. 내 컴퓨터는 확실히 안정적이지 않습니다. 에어컨은 안정적이지 않습니다. 아무것도 없습니다.”

"나는 그것을 좋아한다!" Fuchs를 외쳤다.

다른 사람들도 마찬가지였습니다. QBIST와 QBISSELS 모두에서 세계의 고유 한 불안정성에 대한 회원의 둥근 로빈. 불교와 알프레드 노스 화이트 헤드는지지를 받았다. 나는 혼란 스러웠지만 동정심이 많았습니다. Martina와의 것들이 더 긴장을 풀고있었습니다. 전염병을 통해 함께 사는 것은 피해를 입었습니다. 결혼이 의미가 있는지 의문을 가지기 시작했습니다. Gabi가 옳습니다. 안정적 인 것은 없습니다.

Fuchs가 보통 그의 임박한 칵테일에 대한 소음을 만들기 시작한 시간은 5시였습니다. 나는 스스로 하나를 사용할 수 있었다. 그러나 Qbists는 롤에 있었고 나는 Fuchs가 나를 끝내기를 원한다고 느꼈습니다.

“다음 질문은 무엇이었던 밥”그는 말했다.

나는 숨을 쉬고 수소, 가장 간단한 요소, 그리고 Bohr와 Heisenberg가 그날과 함께 경쟁하는 주파수에 대한 토론을 조종했습니다. 나는 왜 그 주파수가 세상에 대한 객관적인 사실이 아니라면, 우리 모두가 그들이 무엇인지에 대해 동의하는 이유를 이해하고 싶다고 말했다.

“설명해야 할 것이 있습니다. 주관적이라는 것은 무엇을 의미합니까? 그것은 다른 사람들이 다른 의견을 가질 수 있다는 것을 의미합니까?”

Fuchs는“천천히 잃어 버리고 있습니다. “아마도 이것이 내가 당신에게 이메일로 당신에게 대답 한 적이없는 이유 일 것입니다. 우리는 동의 할 때 동의하고 그렇지 않을 때는 동의합니다. 우주에는 우리가 무엇이든 상관없이 어떤 것에 동의해야한다고 말하는 전제 조건이 있다고 상상할 수 없습니다.”

“그러면 대답은 QBism의 바로 바깥에 있습니다. “범위가 떨어집니다. 괜찮습니다.”

몇 가지 반대 의견이 응답하여 나에게 쇠약 해졌지만, Fuchs와 나는 그것을 피했다. 그런 다음 Fuchs는 회의를 마무리했습니다.

"밥, 당신은 생각을 자극하고 있습니다."그가 말했다.

내가 생각했던 것 같은 것은 멍청했다.

QBUKIS, QBISTS와 함께 수많은 일대일이 몇 개 더 걸렸으며, 내가 오래된 사고 방식의 틀에서 벗어날 수 있고 QBIST에게는 와인 유리가 을 깨닫는 데 꽤 많은 시간이 걸렸습니다. 원자로 만들어졌습니다. 일이 예상의 묶음으로 재구성되면, 큰 것들은 믿음이 그렇게 작동하지 않기 때문에 큰 것들로 만들어지지 않습니다. 원자는 대신 성분이 아닌 와인 잔의 측면이되므로 개념 을 의미합니다. 그것은 전자 현미경에서 어떻게 보이는지와 같은 우리의 기대 중 일부를 캡슐화합니다. 그 실현은 Titmouse와의 만남보다 나에게 더 놀라운 또 다른 사람으로 이어졌습니다. 단지 원자보다.

I also appreciated that the point of Fuchs’ car crashes was that all the so-called facts about the world that we glean from observing it are, strictly speaking, beliefs, since future experiences could reveal them to be false. No sensible scientist would disagree, and an irony that I was just starting to perceive about QBism was that its most radical claim is not so much that our facts and ideas are subjective in this way, but that it has identified in quantum theory a single one that is not .

But there was still one big nut I hadn’t cracked:the one that had set Fuchs off at the end of the meeting, the question of why people agree about physical facts if those facts don’t exist objectively. Sure, part of the answer is that as members of the same species, we respond to similar stimuli in similar ways; but that still begs the question of what the sources of those stimuli are, because despite Hollywood’s car crashes and Barreto Lemos’s faulty air conditioning, the world does have stable features, including the existence of my laptop, the characteristic colors of hydrogen gas, and all the other physical phenomena that people with working senses do agree about and that, at least to my way of thinking, quantum theory was originally developed to explain. I mean that’s what science is about, right? Explaining things? Finding truth?

Over the summer, I spoke to several specialists who confirmed that I was not alone in my frustration.

Jean Bricmont is a retired professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium. His books include Making Sense of Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Sense and Nonsense . Bricmont wants to ask the QBists, he told me, “What is your belief about ? They’re subjective beliefs, OK, but about what ?” He didn’t buy my suggestion that QBism was an improvement over Bohr because it solves Wigner’s friend. “It’s an improvement only insofar as it reveals the absurdity [of Bohr’s interpretation],” he said. “It’s pure idealism.”

Oxford philosopher Christopher Timpson has thought deeply and written much about QBism. Although he remains relatively sympathetic to it, he still considers its lack of explanation of physical facts a potential “killer blow.” “If you want, as very plausibly one should want, a thicker notion of explanation which stands independent from merely what we expect,” he said, “then the QBists can’t deliver it unless they make some clever new developments.”

I was particularly eager to hear from Carlton Caves, Fuchs’ old research advisor and collaborator, whose input had been crucial to QBism’s early development. I knew from Fuchs that he’d ultimately lost his enthusiasm for it. 왜? I wondered. “I look out my window and there’s an oak tree there,” Caves told me. “I expect other people to look out my window and tell me there’s an oak tree there, and there’s nothing in QBism that would suggest there’s any reason to think that that would be true.”

Caves had worked with Fuchs and Schack for more than a decade and considers them both “incredibly deep thinkers.” He called their collaboration the “first golden age” of his career. But in the end, the implications of probabilities being beliefs led to a place that was, he said, “not where I want to be.”

Ruediger Schack, the third of QBism’s co-founders, was still a believer. He’s a professor of mathematics at Royal Holloway, University of London. He has a deep voice and an economy of speech that leads Caves to call him “Mr. Terseness” to Fuchs’ “Mr. Prolixity.” When I told Schack that Timpson called QBism’s lack of explanation of physical facts a “killer blow,” his response was, in effect, an indifferent yawn. “QBism can predict that the color of ruby is red,” Schack said. And that, he said, “is all the explanation I need.”

I understood why Caves called him Mr. Terseness. But it was Schack’s equanimity above all that helped me put the final piece of the QBism puzzle in place:It convinced me that Schack’s own craving for explanation had been satisfied. To be able to predict, he was saying, is to have an explanation, not one that’s necessarily simple enough to be summed up in a few sentences, but one that resides nonetheless in all the knowledge and know-how that went into the prediction. William James and his fellow pragmatists would, I believe, have agreed. After all, if our ideas and theories don’t mirror an underlying reality, in what sense can they supply explanations? “Truth in our ideas,” James wrote, “means their power to work.”

Rationalists like me crave mechanistic explanations:A ruby is red because the electrons in its atoms move in a specific way, and anyone looking out Caves’ window will see an oak tree for similar reasons. But when atoms are considered concepts as opposed to constituents of rubies, mechanistic explanations no longer apply. It’s a “stock rationalist trick,” James wrote, to treat concepts we invent to explain phenomena we observe. We could claim, James said, that a man digests and sleeps well because he is healthy. But “healthy” is just a word coined to describe someone who digests and sleeps well, so that claim is no explanation at all. QBists believe that quantum theory validates James’ conceptions of truth and explanation because attempts at mechanistic explanations for quantum phenomena like the double-slit lead to paradoxes—such as electrons being both particles and waves.

I soon found myself applying such pragmatic thinking to day-to-day life, including my disagreements with Martina. What was the point, I thought, of all the “why” questions I was always asking her and myself. Why is it so hard to put things back the way they were? Why am I so bothered that she doesn’t? What I really needed, and what were so often right in front of me, were answers to “How?”

And yet I couldn’t feel satisfied with the notion that knowing how is as good as knowing why in physics, for the same reason that Bricmont dismisses QBism out of hand and that I once called Bohr’s ideas a dead end:It seems to imply that physics ends at human experience and can’t speak to the nature of reality beyond that.

Fuchs disagrees.

It was a steamy morning in July of 2021, in that hopeful period post-vaccines but before Delta. Fuchs was sitting in a white Adirondack chair in his backyard, crossed bare legs and Birkenstocks supporting the laptop in which he was engrossed. I’d driven to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, from mine in upstate New York and we, abiding by long-ingrained middle-aged-guy manners, shook hands. I think he may have been a little nervous. I know I was. I’d never before had such intense interactions with someone I hadn’t even met.

He showed me around his expansive suburban backyard, a charmingly chaotic sprawl of patios, herbs and vegetables growing in pots, fabricated flowers and giant insects made of metal and wood, and the tools and hardware for innumerable partially finished projects, all surrounding a large slate blue house. A big tan and white dog named John Archibald barked nonstop at me until he settled down. Kiki made muffins. And for the next two days Fuchs and I hung out in his yard and house and engaged in the kind of long, free-flowing conversation that you can’t have on Zoom.

After our initial tour, Fuchs recounted how he came to physics. He’d already told me about growing up “pretty poor” in the small Texas town, Cuero, and about a childhood that involved at least as much conflict and confusion as mine. Now he explained how he’d found refuge in science fiction, including Isaac Asimov’s books and Star Trek on TV. He’d dreamed of living the life of Captain Kirk, flying to the stars and exploring strange new worlds. That led him to the physics section of the library, where he went to learn how to make that happen.

“It was like porn for me,” he said about the books he took home. The equations went over his head, but he understood enough to discover the disappointing truth that Einstein’s theory of relativity, and its prohibition on faster-than-light travel, made his Star Trek dream impossible. “The laws of physics aren’t going to allow it,” he recalled telling his best friend. “So they’ve got to be wrong.”

Fuchs explained he was inspired by the scientific writings of physicist John Archibald Wheeler, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Once, while attending the American Legion’s Boys State program in Austin, Fuchs snuck off to meet Wheeler. The professor was out of town, but his secretary let him take a sampling of his papers, including one on an idea called “law without law,” which was that the laws of physics are not hard and fast but rather only approximations that arise from quantum randomness, similar to how order emerges from chaos in Darwin’s theory. It was an idea that offered Fuchs hope that his dream was not dead. As the other John Archibald lolled in the grass nearby, Fuchs stopped at this point in his story. A surge of emotion made it hard for him to speak. “I was like Whoa! ” he said. “I’ve got to understand quantum mechanics!”

Fuchs did his bachelor’s in physics at UT, with Wheeler as his research advisor. He also earned a bachelor’s in mathematics. “It from bit” was another Wheelerism. It expressed his belief that an electron, as Fuchs put it, “is nothing more than our information about it.” Inspired by that idea, Fuchs found his way to Caves and Schack on a mission to understand quantum mechanics in information terms.

While I’d gone into physics seeking something solid to believe in, Fuchs went with precisely the opposite orientation:with hopes of showing that the laws of physics aren’t 단단한. Years later, it seemed that he’d succeeded too well. QBism’s core tenet that probabilities are personal beliefs had led to the conclusion that every part of quantum theory, from quantum states to the lab equipment used to measure them, had the metaphysical status of subjective beliefs, with no apparent foundation in objective reality.

“So where do you go with that?” Fuchs said. “You would think, well, you can’t go anywhere now. Everything is subjective.”

The sound of blue jays jeering came from some nearby trees.

“And then you think on it for a few years,” Fuchs continued, “and then you go, Oh! 오! Quantum probabilities aren’t freewheeling. They’re all tied together!”

This was the insight that led to QBism’s most profound claim:that there is one thing in quantum mechanics that is not subjective, that everyone should agree to. It’s not really a thing but a rule, a new mathematical rule that constrains a person’s choices beyond the restrictions of standard probability theory. To a QBist, this new rule constitutes the essential content of quantum mechanics, and signals what the theory can tell us about the nature of reality, even beyond human experience. The rule’s most crucial feature is that it is “normative,” meaning that it tells the theory’s user how to think rather than how the world behaves. Fuchs’ compares it to the Ten Commandments. One can disregard it, but “something bad is likely to happen as a result.” “Bad” meaning that your computer, nuclear reactor, MRI machine, or any other application of the theory simply won’t work.

We were now in Fuchs’ living room, him on his sofa, bare feet on the coffee table, and me in a chair nearby. I asked him what the normative character of quantum theory’s new rule says about nature’s doings. That their probabilities “can’t be quantified,” he said, that “there’s no number that will shoehorn a potential event.”

I was reminded of something I’d read before. “Nature and its parts do what they want,” Fuchs had written, “and we as free-willed agents do what we can get away with.”

Fuchs sounded a lot like James, who speculated that “experience as a whole is self-containing and leans on nothing,” meaning that no deeper layer of reality explains our experiences, because the experiences themselves comprise the ultimate reality. James called his vision a “pluriverse,” a place in which no thing was more fundamental than any other, where mental phenomena like dreams and ambitions are as real and substantive as anything else, and where, he wrote, “being comes in local spots and patches which add themselves or stay away at random, independently of the rest.” James’ pluriverse was the furthest thing imaginable from what he called the “block universe,” one that amounted to a giant machine, built from fundamental ingredients and governed by immutable laws. The pluriverse was a wilder and more heterogeneous place, one that was forever unfinished as its motley cast of constituents pushed, pulled, and clashed with each other in a never-ending process of construction, each driven by its own unknowable inner nature, each free from the reins of any top-down laws at all.

This is Fuchs’ understanding of the world, too. “I think the chair that I have my feet on has as much of an inner life as I do,” he’d said in one QBuki.

Our conversation circled back to Wigner’s friend. Fuchs compared the scenario to one of those Escher drawings, of say a staircase, which displays in two dimensions a situation that can’t exist in three. In the analogy, Wigner’s and his friend’s contradicting facts are like two sections of the staircase:They can peaceably co-exist so long as we don’t try to interpret them as aspects of a single block universe.

I was finally appreciating how quantum theory could substantiate the pluriverse idea. How James’ “experiences” and Bohr’s “phenomena” could be one and the same. How quantum theory’s mysterious acts of “observation” could correspond to James’ “facts in the making.” And how it might be that there are no variables hidden in Heisenberg’s black box, because reality is simply the phenomena, the experiences, out of which that box was built—and more generally that there may not be any deeper reality hidden in the palace of ideas because it too is derived from experiences and not the other way around.

And I could see why Fuchs kept saying that quantum theory makes life worth living. “The world stands really malleable,” wrote James, “waiting to receive its final touches at our hands. Like the kingdom of heaven, it suffers human violence willingly. Man engenders truths upon it.”

It’s that malleability that gives Fuchs hope, because to him it means that the laws of physics only summarize the experiences humans have had so far, do not limit those we may have in the future, and are even, to some extent, shaped by human activity. “One day we will get to the stars, in the sense of Star Trek ,” he said from his sofa. “How’s that going to happen? I don’t know … But if you buy the ideas of James … then you’ve bought into a hope that it can happen.”

Hope, yes, but as to going further, Fuchs unfortunately is “stuck.” He told me this a couple of weeks earlier in a one-on-one Zoom call, while wearing a “Life is Crap” T-shirt illustrated with a cartoon bird pooping on a sad face. I’d run my fifth and final QBuki a few days before and he’d written me an email saying he felt sorry for me, because of how exhausted I looked by the end. He suggested we talk to try and iron things out.

His tone was completely different than I’d ever heard before. He spoke to me as if were colleagues rather than like an oracle, speaking down from above. He confessed that the QBism project was stuck and explained why he’d snapped at me in the QBuki a few days before. “You got my ire because you, poor fellow, made the poor choice of word ‘repeatability,’ ” he said. Repeatability just meant the ability of scientists to repeat experiments. What was wrong with using that word? “Well,” he said, “I’m trying to construct a philosophy where nothing is repeatable, where the world is fresh in every moment.”

Trying to construct . I suddenly realized how much of QBism is a product of Fuchs’ desire and how much its future depends on faith. Fuchs went on to tell me a story he’d written a long time ago which, although he’s an atheist, recounted a conversation between Adam and God. Adam wishes for a world like Fuchs wants to believe in. And God grants his wish by making the world conform to quantum theory, such that it grows unbound by laws as James envisioned, and yet where science can progress by finding normative rules to navigate it, including potentially to the stars. “Faith uses a logic altogether different from reason’s logic,” James wrote. “Reason claims certainty and finality for her conclusions. Faith is satisfied if hers seem probable and practically wise.”

Fuchs said he abides by the chain of thinking of James’ faith ladder:

“It would be well if it were true …”

“It might be true …”

“It ought to be true …”

“It shall be true,” goes the last step:Act as if it is and it will be.

Fuchs and his QBists are now looking for ways to flesh out fuzzy philosophical ideas like “experience,” to translate them into mathematical language, and to show in detail how quantum mechanics follows from them, which is to say to explain why that particular theory is the optimal “law of thought” to survive and thrive in the pluriverse. How to go about that is not at all clear.

“I think there is a better story to be told,” Fuchs said across the coffee table, “but we don’t know how to do it yet.”

We talked for a long time about the challenges of abandoning a God’s-eye view when thinking through situations like Wigner’s friend. What, after all, is “the” situation if all that is real are Wigner’s and his friend’s individual experiences? I said I couldn’t see how to think that way. “It’s a struggle for me too,” Fuchs said. “You’re asking tough questions. You really are a member of the group.”

Maybe he was being polite. But I believed him— even if I wasn’t quite ready to take the leap of faith that a true QBist needs to make.

A week after I left Fuchs, on a vast green lawn overlooking the Hudson River and the Catskill Mountains beyond, Martina and I stood under an arch of white flowers and exchanged vows in front of our families and friends. Although I had a lot of things on my mind in the preceding days, one was how to think more like a QBist.

I chuckled at an irony. I’d started off hoping to understand QBism’s way of reconciling the familiar everyday world with the foreign quantum one and ended up open to the idea that we’re all living in the quantum world. How much my new outlook came from Fuchs versus my love for Martina was impossible to know—my thoughts and feelings were too entangled to separate. But it seemed right, as QBism claims, that the everyday and quantum worlds are one and the same. That uncertainty is unavoidable and unquantifiable. That people can have different realities but must live in the same universe. That we are more than just atoms. That our choices are our own. And that our futures are not limited by our pasts.

It ought to be true …

Bob Henderson is a writer based in upstate New York who earned a Ph.D. in theoretical physics, and has previously made his living as a photojournalist, electrical engineer, financial quantitative analyst, and derivatives trader.